How does one tend to a plant which glorifies war, plays a minor role in nationalist propaganda, or is laden with personal grief? This question has been on my mind since attending Gabriella Hirst’s workshop at the NY Art Book Fair.

Battlefield

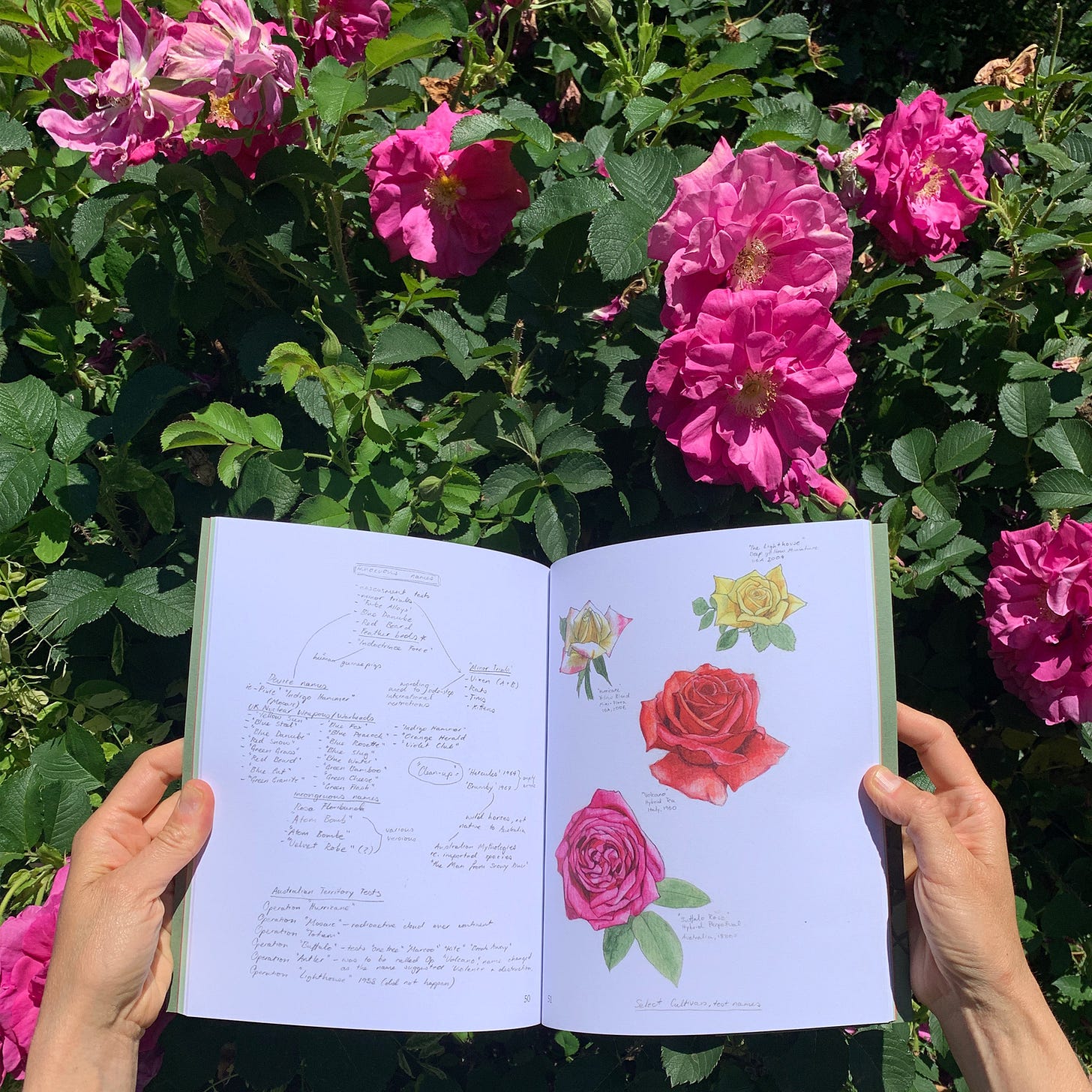

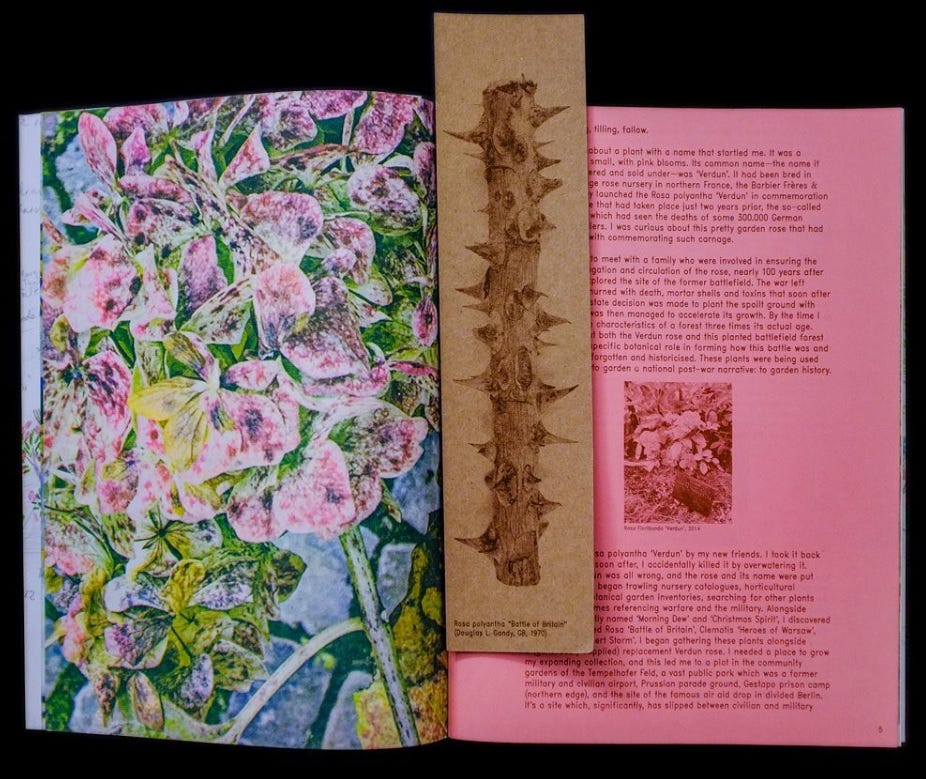

In 2013, Gabriella Hirst stumbled upon a pretty garden rose with a shocking name and a heavy burden. The flower had been cultivated in 1918, and sold under the name Rosa polyantha ‘Verdun’.

‘The Hell of Verdun’ was a WWI battle that resulted in the death of 300,000 soldiers. It was only 2 years after the carnage that a nursery in France launched this rose in commemoration.

Hirst visited the family of propagators and the battlefield. She states: ‘The war left these soils churned with death, mortar shells and toxins that soon after the armistice a state decision was made to plant the spoilt ground with a forest’.

‘I understood that both the Verdun rose and this planted battlefield forest were playing a specific botanical role in forming how this battle was and is remembered, forgotten and historicized. These plants were being used to garden grief, to garden a national post-war narrative: to garden history’.

A Living (and Dying) Archive

After this encounter, she began searching for other varieties that had officially registered cultivar names referencing warfare, battles, and armed conflict in nursery catalogs, horticultural registries, and botanical garden inventories.

Her sprawling index of almost 200 species includes names such as:

Apricot ‘Samurai’

Clematis ‘Heroes of Warsaw’

Daffodil ‘Desert Storm’

Dahlia ‘Flame Thrower’

Daylily ‘Mandatory Evacuation’

Fuchsia ‘Friendly Fire’

Iris ‘Grenade’

Peony ‘Bunker Hill’

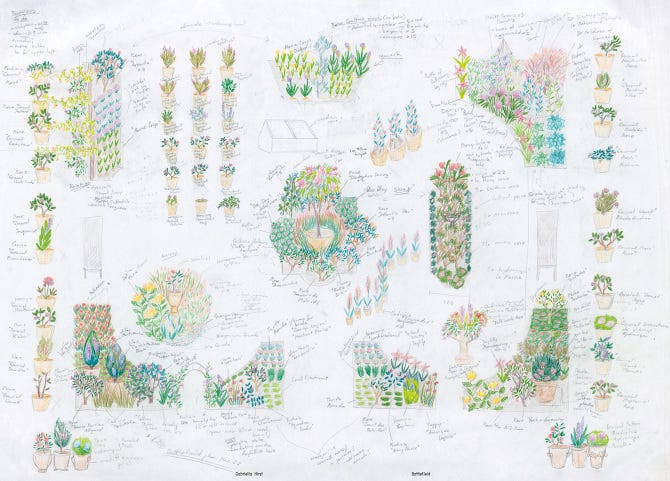

Her growing collection eventually found a home in Germany at Tempelhofer Feld, a site of military practice, parade ground, prison camp, and aid drop in divided Berlin. It has since served as a civilian airport, public park, community garden, and an arrival center for refugees.

The project has also had iterations in Kunsthalle Osnabrück, a former cloister, and now at the Augustaschacht Memorial, a former Nazi site of forced labor.

An English Garden

In 2021, Hirst was commissioned to install a garden of cold war-era roses and irises in Gunners Park, England. The manicured gardens in the UK are renowned worldwide, a showcase of soft power.

Hirst highlights: ‘the english garden is entangled with a violent past of gardening the world’. England’s settler identity is rooted in conquering places that need to be ‘managed’. The mundane maintenance of a garden is an aesthetic practice of dominion over nature.

The garden’s layout mimicked military architecture and aerial maps of contaminated nuclear test sites. The benches were an invitation to reflect on Britain’s imperial history, colonial legacy, and its looming effect on the present.

The artwork was forcibly removed after local conservative politicians gave Hirst’s team 48 hours to take it down before personally intervening. They viewed its message as a left-wing attack that required censorship.

‘Seemingly, said government and its global-scale nuclear arsenal was not considered robust enough to endure the airing of historical facts and critique via a rose garden art installation’.

The Political Symbolism of Plants

Another contentious point is sifting between the stories and speculations as to why these flowers have such visceral names. Most were cultivated in the last 500 years by European plant breeders and hybridizers. Their reasons vary:

Reflect the politics of the breeder

Boost sales as a marketing strategy

Appeal to bereaved families

Sell en masse to state cemeteries

The names can be a double-edged sword. How they’re perceived depends on public sentiment at the time. Do they honor or are they horrifying? Hirst adds further nuance to this question:

‘Was this plant registered ‘Memory of Malmedy’ intended as a memorial for the infamous massacre that took place in Belgium, or was the breeder commemorating personal peaceful memories of the same place? When the breeder of a bright yellow echinacea flower named their new creation ‘Grenade’, were they thinking of the imagined aesthetics of the exploding weapon? Or the fruit after which the weapon was named in the 1500s?’

Gardening Language

It’s not just the names of this flora that have violent roots. The multiple ways we subject and submit plants to ‘order’ are emphasized in our conflictive language around gardening. We create borders, divide, graft, pinch, prick, weed out, etc.

The language of destruction and rejuvenation blurs. The same goes for the language of garden care itself: to ‘strike’, ‘defend’, ‘plough’, ‘compost’, ‘till’, ‘sow’, ‘reap’, and ‘prune’. ‘Trenches’ are dug. Species are ‘invasive’. We ‘defend’ saplings against pests and ‘force’ growth from them in greenhouses.

Even within botanical and horticultural studies, we uphold colonial ways of organizing the world and enforcing naming structures. We confine species to an area, we upkeep signs, and we create contained archives to keep the subjects still, unchanging, within control. The language of warfare is insidious.

History is a Continuum

Acts of organized violence are not isolated incidents. Land and language are deployed for both civilian and military use. Our governments then craft how events are memorialized which shapes how we remember, or ignore, history.

Flowers can serve as an ephemeral monument. The garden becomes a site of collective memory & cultural heritage. In these places, visitors can view the past with romanticism or confront its future repercussions.

‘I wonder if the land, and its battlefields, have been gardened in a way that the Colony may forget this history. Perhaps I am intrigued by the battle-named plants because they carry history of violence in a way that is legible for me in an obvious way—the past emblazoned upon official botanical labels. Grown together, these plants create a history book—flawed and limited and messy anthology, embedded in the green’.

The Garden as Site of Critique & Care

The act of gardening is important in Hirst’s process. The continuous caretaking allows space to sit with the tension that emerges as she tends to these plants and the fraught history they carry. She contemplates whether these gardening practices uncover what lies underneath or provide a false sense of peace. A battle of the earth between conquest and care.

How can we compost complex histories of bloodshed & weaponry over time?

How have we forcefully neutralized, sanitized, or pushed away that which repels us? How can we bring it to light with tenderness?

How to take care of that which we would prefer to bury?

‘There is no final answer to this, no still life, just the continuum of season after season.’

I'm deeply grateful for the seed links that you have shared here.

I am a British seed that grew in a Pakistani womb. My British-South Asian womb was the fertile soil for my Palestinian babies to grow.

We now find ourselves the guardians of some land in Northern Italy. We intend to grow Molokhia in this soil. I think it could thrive here. The children seem to be 🌱💚🌿

Qué texto tan provocador, Leila. Gracias por escribirlo. Espero con ansias el que sigue. Abrazos enormes.